Satirising Land

In April 2019, academics, activists, journalists, writers, poets, filmmakers, singers, composers and others with an interest in ecology and sustainability, came together to discuss the many lives of land. A cartoonist sketched our discussions, held over two days at the International Centre Goa, western India.

Land has many lives. It has multiple forms, meanings, and uses, and it is intertwined with the human and non-human world. If we care to listen and feel, land tells stories and reveals its multi-dimensionality.

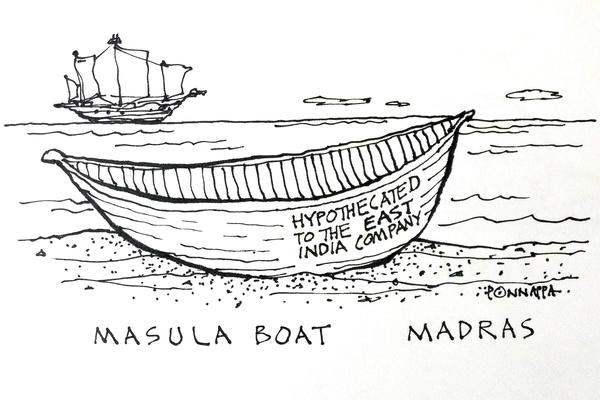

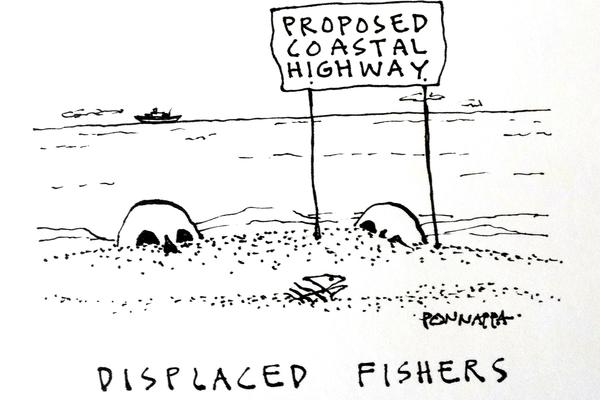

Land is steeped in history. The coast of Chennai in southern India is being eyed by large port and infrastructure projects today. These projects are promoted under the rubric of development. The coast is framed as wasteland that will be built into value. But this very coast was once the repository of colonial trade. Small fishing boats called ‘masula boats’ plied between the large ships of the East India Company and the shoreline of Chennai. The boats were operated by local fishers. These fishers are today dismissed as poramboke or ‘waste’, much like the land they live and fish from. They will have little place in the automated economies of New India.

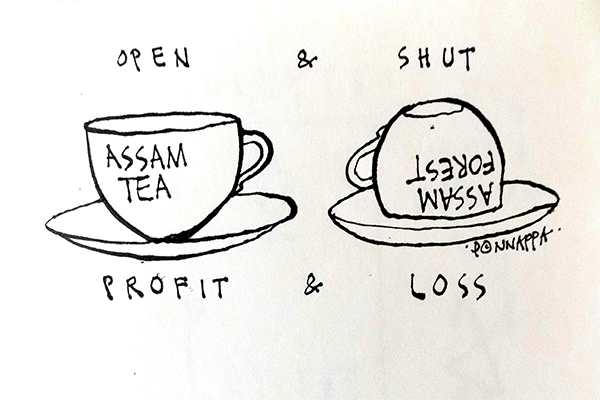

Just as the coast of Tamil Nadu was harnessed for the trade-centric colonial project, the fluvial lands of Assam too were tapped for emerging plantation economies. The systems of land administration that were put in place by the colonial order continue to shape the history, economy and politics of Assam till date.

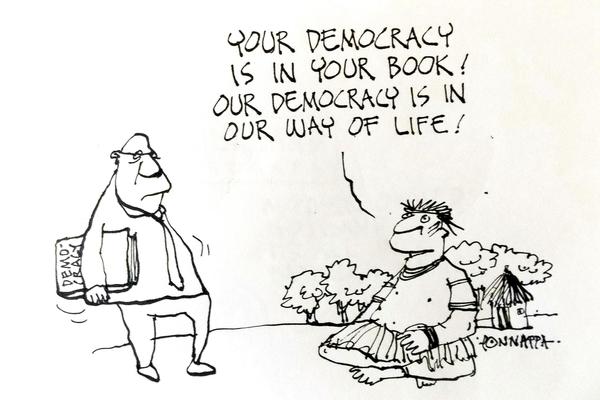

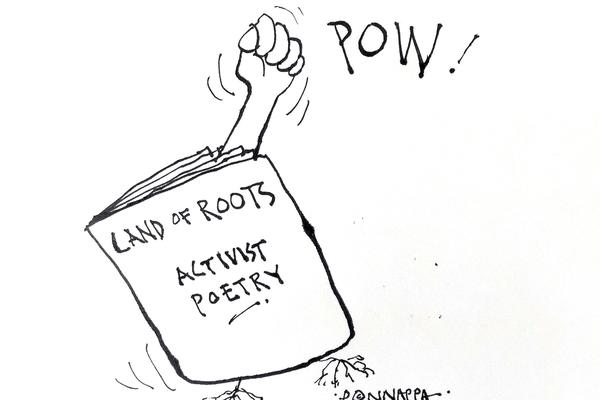

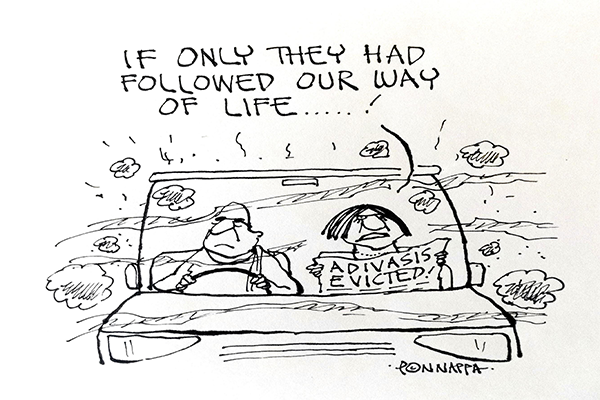

Colonial and postcolonial rule over land—with its will to capture and control nature—has many opponents. Adivasis, the indigenous or original inhabitants of India, have suffered dispossession and displacement at the altar of development. They are increasingly, and very creatively, questioning the logic under which land is governed and distributed. Their voices are even more salient in the era of climate change.

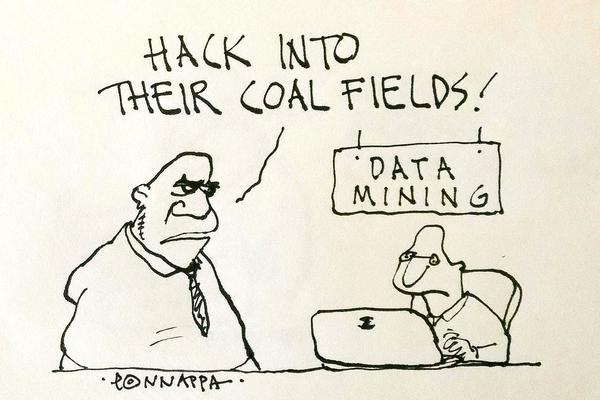

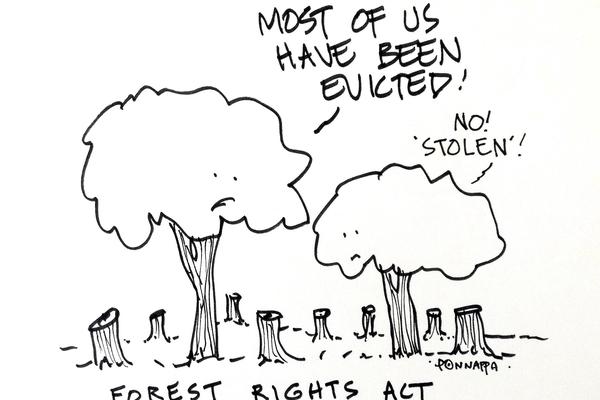

Over time, the postcolonial Indian state has enacted legislation to protect land, forests, and the people whose lives are entangled with these. However, the logic of profit often trumps all other considerations. Adivasis and others are protesting the dilution of progressive legislation such as the Forest Rights Act and the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act. These dilutions favour industry, infrastructure, real estate and mining projects. They are poised to further alienate the majority of the population from their land and nature.

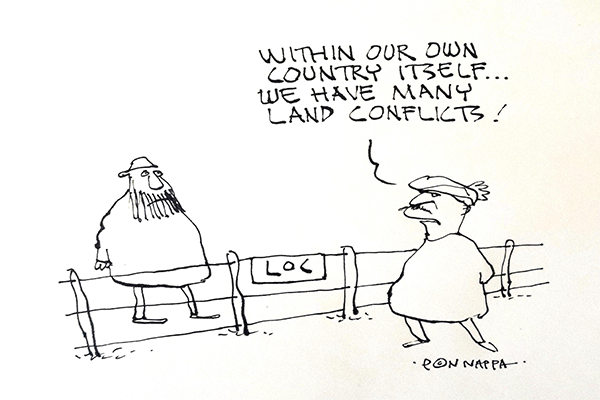

Even as land as history, and land as possession and dispossession are hotly debated in India, land as national territory is built up as almost sacred. The defence of this land becomes all-consuming, sometimes papering over the struggles within.

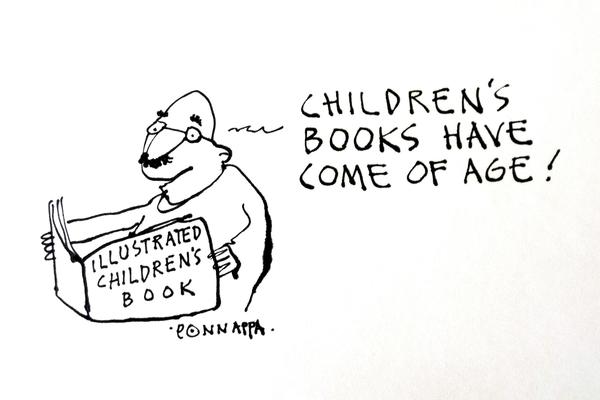

A group that is symbolically revered along with the motherland are women, but only in the garb of mothers and daughters to be sheltered in a largely patriarchal society. Wars are fought over mothers, and the land, and elections are won and lost over their protection. Isn’t it ironic that both land, and the women of this land, are treated so shoddily?

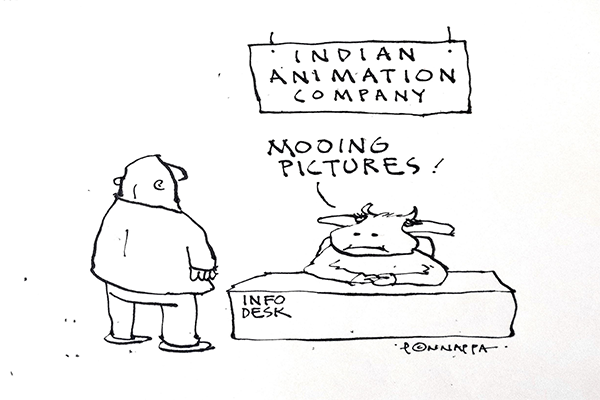

As marginalised groups struggle to be part of the unfolding story of India’s land, what of its non-human inhabitants?

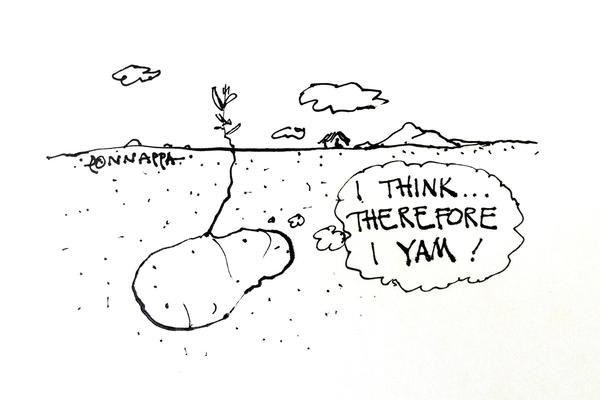

Land is multi-faceted. It is history and memory. It is state authority and territory. It is to be contested, controlled, revered, won and lost. But land is also nature; it is life itself. Humans have for long tried to control land, and the narrative around land. We have even divided the earth into private property. If we are not to become trapped in our own narrative of being all-powerful masters of the universe, we need creative ways to re-engage with land multi-dimensionally. The many lives and stories of land must be gathered from, and told to, as wide an audience as possible.

Text: Nikita Sud

Illustration: Nala Ponnappa